Scientific Commentary on a Paper about Monocyte-macrophage origin and renewal

By Mingzhen Tian

原文链接:Fate Mapping via Ms4a3-Expression History Traces

Monocyte-Derived Cells

This article recommended by Professor Bing Su is about development of monocytes in the bone marrow and renewal of tissue-resident macrophage. The authors of this article identified specific expression of Ms4a3 in GMPs and used this to construct several lineage tracer models. With these models, they precisely determine the contribution of different monocytes to the RTM pool. They resolved a long-standing controversy in the international immunology community regarding the origin and renewal of monocyte-macrophages. I will present the study background and results in depth below.

Tissue-resident macrophages (RTMs) are a class of cells that are important in homeostasis and inflammation. RTMs have long been thought to develop from circulating monocytes in the blood after entering the tissues. However, new studies suggest that most RTMs are produced by the embryonic hematopoietic system and are then localized to the tissues where they renew and maintain themselves. Therefore, there has been controversy about monocyte-macrophage origin and renewal, and the extent of monocyte contribution to different tissue macrophages has not been elucidated. This article then accurately identifies the origin of RTMs in different situations.

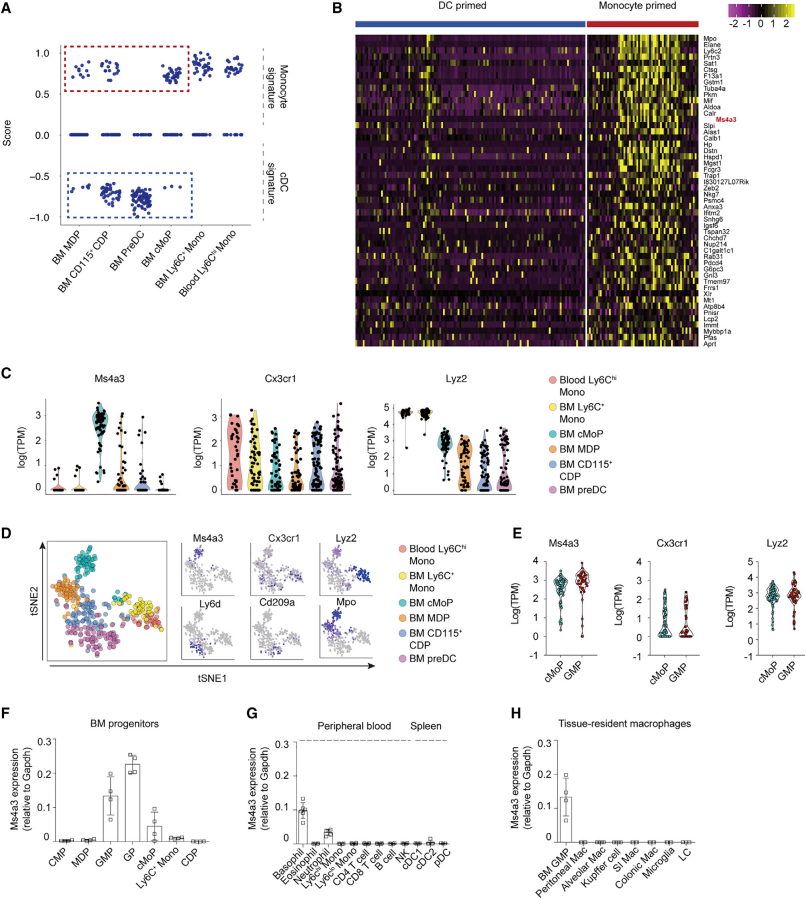

To study the origin of RTMs, we must first know the origin of monocytes. So, the researchers first wanted to construct a mouse model that could track monocyte progenitors. This process requires the identification of a gene that is expressed only in cMoPs and monocytes but not in DC progenitors. They performed single cell transcriptome analysis of immune cells after flow sorting. By analyzing transcriptomic signatures, they found that MDPs are monocytic lineage. Next, by analyzing DEGs from DC progenitors and monocyte progenitors, they selected a candidate gene Ms4a3. The tSNE map also confirmed that Ms4a3 was specifically expressed in cMoPs. In addition, Ms4a3 is also expressed in GMPs and GPs, indicating that it is a very good tracer of monocyte lineage. The investigators also confirmed that Ms4a3 is not expressed in mature RTMs and DCs.

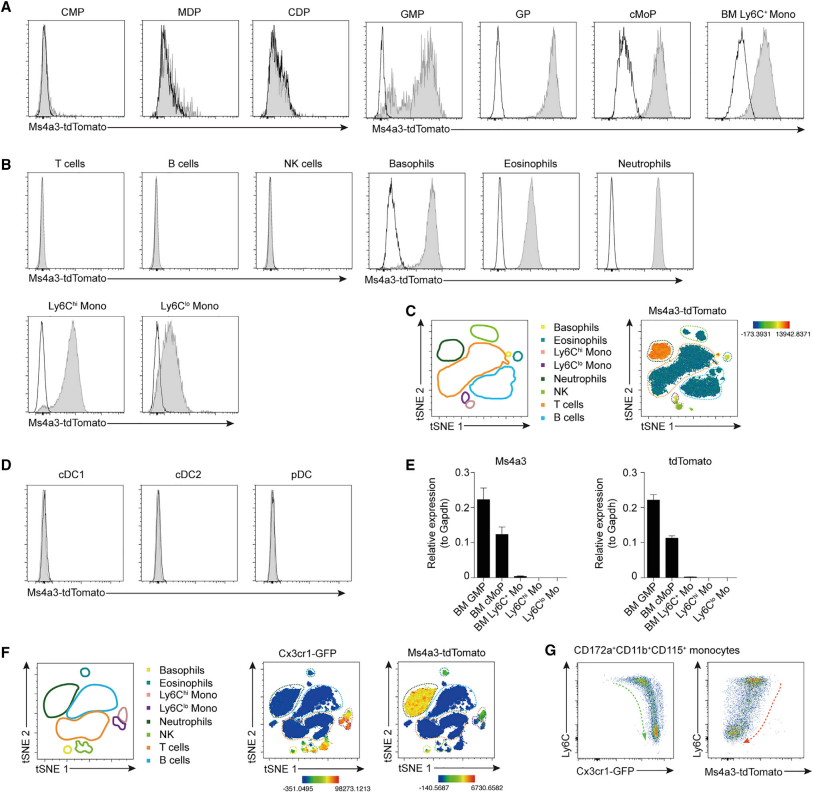

Next, to track the expression of Ms4a3, the investigators constructed the Ms4a3TdT mice. By assay, they found that tdTomato signaling first appeared in GMPs and could be detected in cMoPs and monocytes. In addition, tdTomato was expressed in peripheral blood basophils and neutrophils, but not in DCs. Next, they found that GFP overlaps with tdTomato only for monocytes and cells in peripheral blood by comparison with monocyte reporter mice Cx3cr1gfp. These results suggest that Ms4a3 is a good model for tracing monocytes and their progenitors.

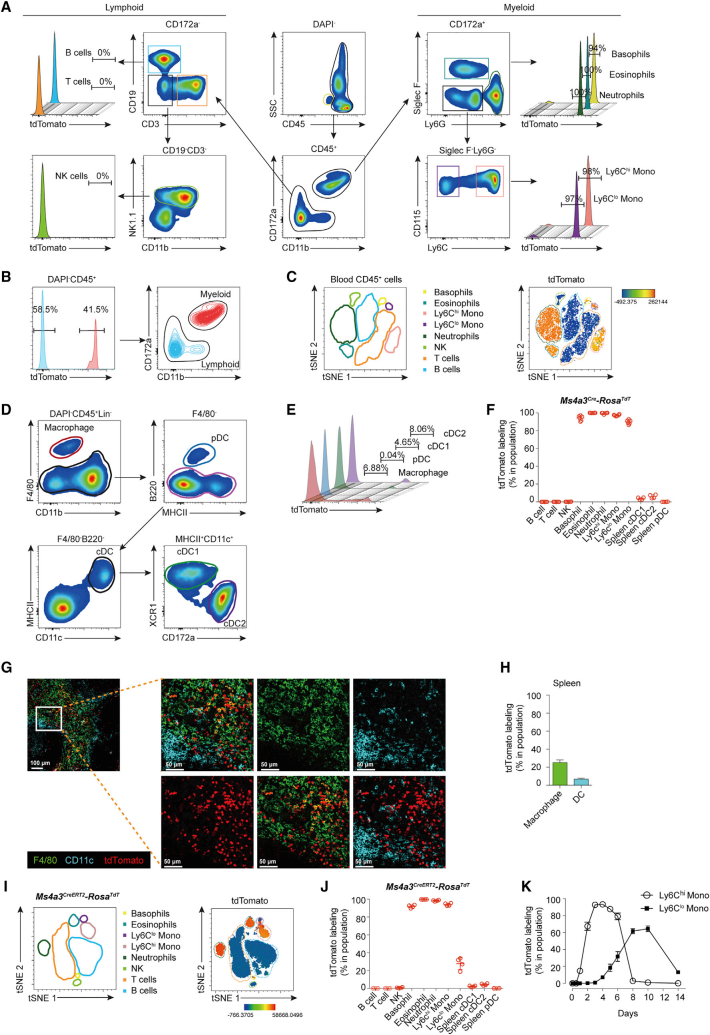

Next, to track the expression of Ms4a3, the investigators constructed the Ms4a3Cre-RosaTdT mice model. This model allows the progeny of cells expressing Ms4a3 to produce red fluorescent markers, thus showing their lineage. By detecting fluorescence after tamoxifen induction, they found fluorescence in granulocytes and monocytes, but not in lymphocytes and DCs. This shows that Ms4a3Cre-RosaTdT model is a good tracer model.

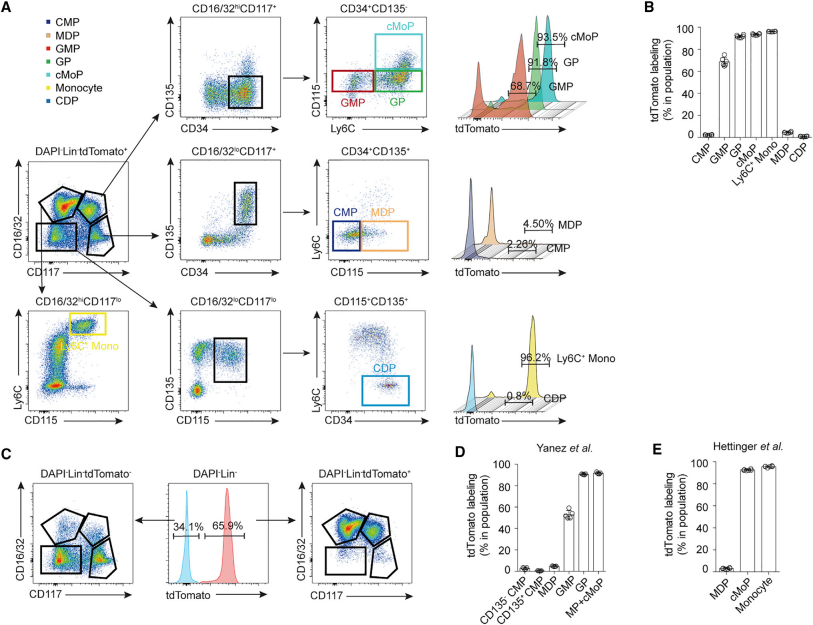

Some discoveries in recent years are gradually challenging the classical developmental pathway of monocytes. Recent studies show that MDPs develop directly from CMPs, not GMPs. By detecting tdTomato levels in monocyte precursors, they found that GMPs were the first to be detected, followed by GMPs progenies, while it is not detected in MDPs. These results indicate that MDPs are not generated by GMPs, but directly by CMPs.

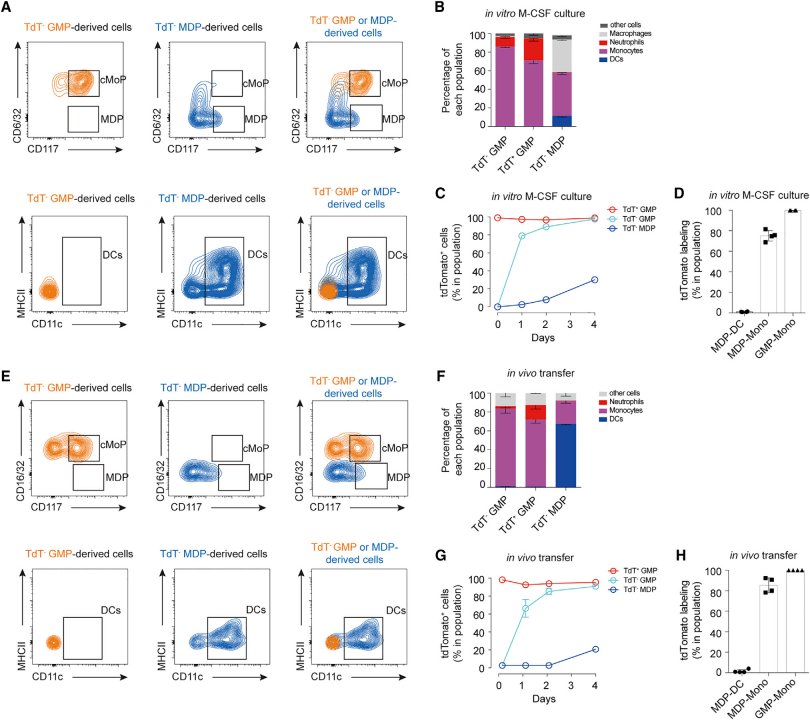

Then they further investigated the origin of MDPs. They first found that MDPs cannot originate from tdTomato- GMPs in vitro. They then verified that MDP-derived monocytes could also be labeled with Ms4a3. They also verified these results in in vivo experiments. Notably, they found that MDPs can develop directly into monocytes without undergoing the cMoP stage.

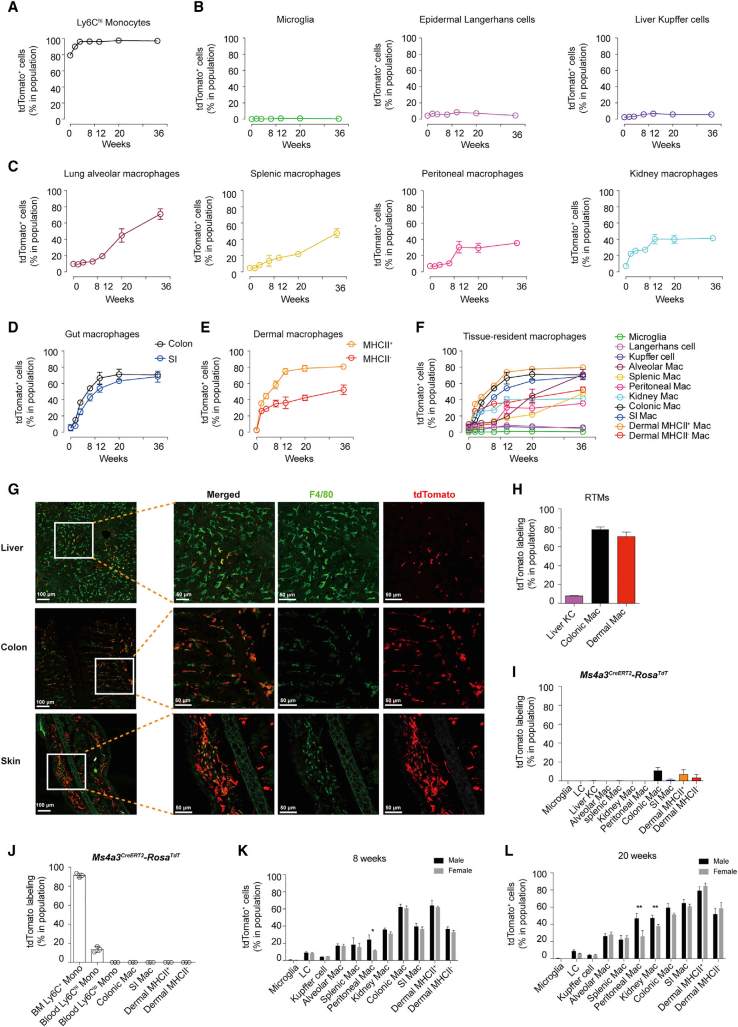

Their study next moved to the second part, the contribution of monocytes to RTMs. They analyzed the levels of tdTomato in different organs and at different ages in Ms4a3Cre-RosaTdT mice. They found that the contribution of different monocytes to RTMs was organ-specific. Organs contributing significantly are kidney, peritoneal cavity, spleen and lung. The contribution in colon and dermal macrophages is also significant and fast. Gender bias was also found in peritoneal and renal macrophages.

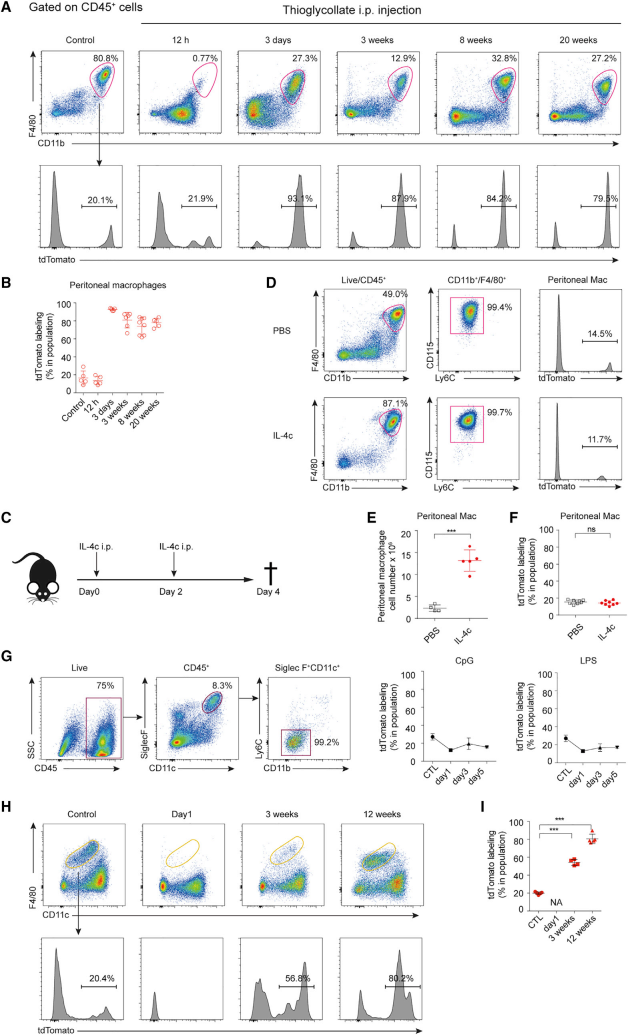

The investigators then investigated the contribution of monocytes to RTMs during inflammation. They constructed five different inflammation scenarios and tested each for tdTomoto. They found that Monocytes can develop into peritoneal macrophages in thioglycolic acid-induced peritonitis scenarios. In contrast, in the IL-4c scenario, the macrophages produced do not exhibit tdTomoto, indicating the absence of blood-derived monocytes. These different results suggest that blood monocytes can complement macrophages in the inflammatory response, but this ability is determined by the type of inflammation.

Overall, this article constructs a reporter model and fate tracing models for monocytes. With these models, the authors precisely identified the development of monocytes and the origin of RTMs during hematopoiesis and inflammation. This is an important guide for therapy regimens targeting monocyte-macrophages. These novel tracer models are also leading the way in the field.

After reading this article, I admire the author’s clever and skillful use of flow cytometry. Single-cell sequencing complemented by biomimetic analysis is also appealing to me. Most importantly, I was impressed by the author’s innovative thinking and diligent efforts.